Those of us who choose to work in pricing love data. We’re awesome at creating reports and charts, and if someone has a question about how to use Excel, we’re the ones you want to talk to.

So when we’re trying to convince the sales team to adjust their approach to pricing, our natural tendency is to start throwing fistfuls of data at them. Maybe even buckets of data. Heck, some of you are showing up with huge semi-trailers full of data that you’re dumping in their laps.

And then the sales team ignores all of it.

This phenomenon can be truly exasperating if you’re not expecting it. After all, we’re taught from our earliest days in school that a longer paper is better than a shorter one. Teachers handed out writing assignments with minimum length requirements, and only the worst students failed to reach those minimums. More data, more words, more well-reasoned arguments should be more persuasive, right?

Unfortunately, that early training doesn’t set us up for success in the business world. More words aren’t always better. In fact, a lot of the time, fewer words are more effective.

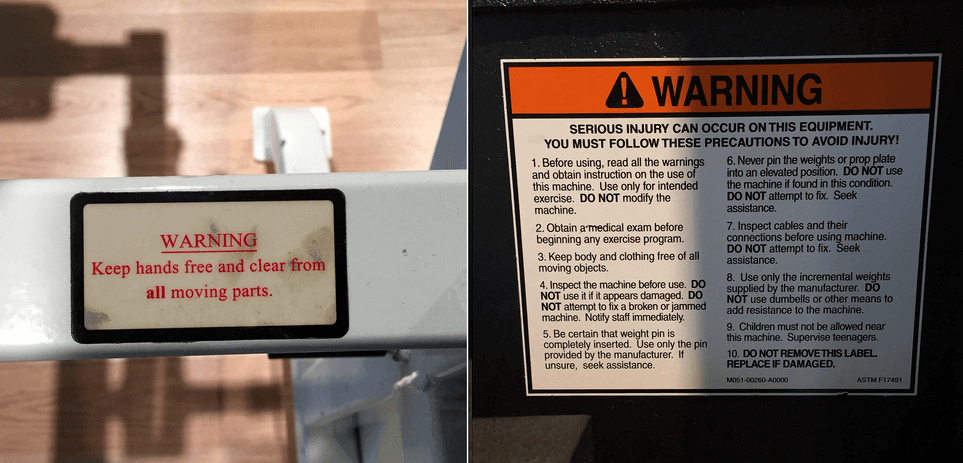

This simple picture helps illustrate why:

The warning label on the left is the kind you were likely to see on gym equipment in the 1980s. If you saw this, you would read it, and understand that you might get hurt if you were dumb enough to stick your fingers too close to the machine.

The warning label on the right is the kind companies are required to put on gym equipment today. You probably didn’t read the whole thing. To tell the truth, I’m writing this blog post, and I didn’t even read the whole thing. This kind of warning is good for protecting companies from lawsuits, but not so great at getting people to take action.

But these two pictures also illustrate another point that isn’t quite as obvious: crafting a message that is both simple and comprehensive is really hard.

The same principle is at work when the pricing team is interacting with the sales team.

The lefthand picture conveys one point really well. But it skips over a lot of important information — like the need to make sure the weight pin is fully inserted. Conveying that information quickly and effectively would require a lot more work. Specifically, it would require us to put ourselves in the place of the person working out. To consider their needs. Their attention span. Their fears. And then communicate effectively in a way that takes that information into account.

The same principle is at work when the sales ops team is interacting with the sales team.

- If we’re providing pricing guidance, we need to think about how the salespeople currently make pricing decisions. Then we need to determine what information they need and how that information should be delivered to get them to make better pricing decisions.

- If we’re trying to explain the rationale behind a price increase, we need to focus on the value perception of the potential customer — not on all the details and descriptions of the various cost factors involved.

- If we’re trying to optimize pricing strategies for different customer segments, we need to figure out how to present the data in a way that highlights the opportunities and risks associated with each segment — not just expect them to apply a one-size-fits-all approach.

We cover these ideas in a lot more detail in a trio of resources:

- Delivering No-Brainer Pricing Guidance

- Survival Strategies for Raising Prices

- Profitable Pricing Enablement

In short, dumping data on the sales team isn’t going to get them to adjust how they think about pricing. It is possible to get them to change — but it’s going to require a lot of time and effort. And in the end, that effort is worth it because it will ultimately help your team — and your entire organization — accomplish its goals.